I have reflected a lot on the use of online lectures, delivered by teaching staff within a specific subject. My questions stem from some analysis a few years ago whereby it became clear that the time I spent preparing for and delivering lectures for online students was potentially wasted. Students weren’t watching them, or if they were, our analytics told us that they were only watching sporadically.

It’s a common issue for higher education educators. It is particularly problematic if we’re requiring students to watch the lectures as preparation for assessment or exams. Anyone following the Twitter feed associated with #academictwitter will be familiar with the discourse surrounding students not reading the syllabus or ‘coming to class’, an online lecture being the online version of that on-campus class.

I have been paring back on online lectures for some time now, but in 2018, I ditched the regular weekly hour-based online lectures. Time-wise, that’s a saving of approximately 30 hours per term, based on two hours per week preparation and delivery, and then a few hours for the rendering, upload, and linking of the video to the subject’s learning management site.

I decided to use this time differently. I will reflect on some strategies I implemented to use this time more effectively on this blog in forthcoming weeks, but they included making time for personal contact after marking student work, and public drafting.

The question became: How do I communicate critical information to students online in a way that communicates a strong sense of presence, but in a way that is most useful for students and time effective for staff?

The starting point for ‘content’

I base my online teaching on a succinct study guide. The study guide is a simple, downloadable PDF converted from a plain MS Word document. Comprising four to six pages, it is a curation of critical points, readings, and activities. The file is not just a list, but the equivalent of a written lecture. I keep the design and approach super-plain, as many of my students are regionally-based and still struggle with access to the internet or the cost of data. I am still very wary of online lessons that look great but still don’t meet the requirements of what I’ll refer to as ‘pragmatic online teaching’ for rural, regional, and remote students (RRR).

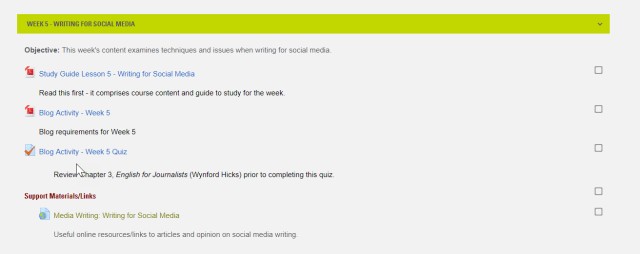

This file is supported by minimal links. An example is below:

You will notice here a link in Support Materials/Links.

This is a link to a social media curation tool, whereby I curate links and provide a short narration as to why they are useful. I used to use Storify, but have been trialling Wakelet as an alernative which seems to be OK. One curated link is preferable, I think, to a long list of possible readings.

Students therefore have a simple, easy to access content. No ‘bangs and whistles’. Just a guide to learning.

Establishing ‘presence’ for online students

In my view, we need to be there for students, but we also need to have a life. It’s easy to over-deliver, and that’s frustrating for students AND staff.

I have contained online teaching time to virtual class hours for many years now. During term, I always schedule these on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. My Monday morning ‘virtual class hours’ are particularly important. They set me and the student up for the rest of the week. During this period, I routinely post a ‘Welcome to the Week’ forum post. Prior to 2018, I also scheduled regular online sessions – fortnightly generally, but sometimes weekly.

In 2018, I bit the bullet and decided to trial a different approach. I decided to replace routine weekly lectures with a more restricted online presence.

I recorded a three-minute video to include with the weekly post. This video specifically addressed the question: Why this week’s content is important for your assessment in this subject, and what the common issues are. I kept it simple – I recorded it directly on my laptop (PC) using ‘Recorder’ and uploaded the mp3 file as an embedded link within Moodle.

It takes me around 10 – 15 minutes to record these short videos.

To support this, I scheduled three to four online ‘drop-in’ sessions for students during the term. In ‘drop-in’ sessions, I sit online and wait for students to ‘visit’ with questions. (I use Zoom for this, which I love as do students.) I find most students don’t avail themselves of the online drop in sessions, but some do and that’s fine. I know there’s some rhetoric about needing to encourage students to come to consultation, but I have some flipped thinking on that. The more students requiring support to understand the task, the more questions I would ask about my assessment design and delivery approach. I don’t want to be a ‘set and forget’ teacher, but my subjects should be easy enough to study from a ‘set and forget’ perspective as a student.

My aim is to be available, but to have designed things so well that the students don’t really need me.

The trial in 2018 worked. My satisfaction scores in 2018 were 4.8 and 4.9 (out of 5 in a Likert style evaluation scale) in both subjects I teach (noting I also have a managerial role now, so teaching is not my core job). Satisfaction, though, isn’t the only measure – I’m interested in impact. I was particularly interested in the improvement in grades in one practically-oriented writing unit. In this, students pitch their ideas in an online session early in the term, prior to writing a personal and news feature. High Distinction grades increased from 37% in 2017 to 53% in 2018, despite lectures being removed. [Note, I am aware of the very high percentage here of high grades, and requested validation of quality through external review. Many student assignments were also published in real publications].

The lesson here was that I could successfully adapt my teaching practice. This meant I could invest more time on valuable tasks such as providing feedback to public drafts, and less time in preparing lectures for a very small group of students who turn up, rendering me a private tutor to a few proactive students.

What happened, I believe, is that all students felt a greater sense of presence, despite the fact that the actual time I devoted to that presence was shorter.

Overall, it was a reminder that we do need to challenge established delivery models which may ultimately save me time and result in positive outcomes for students.